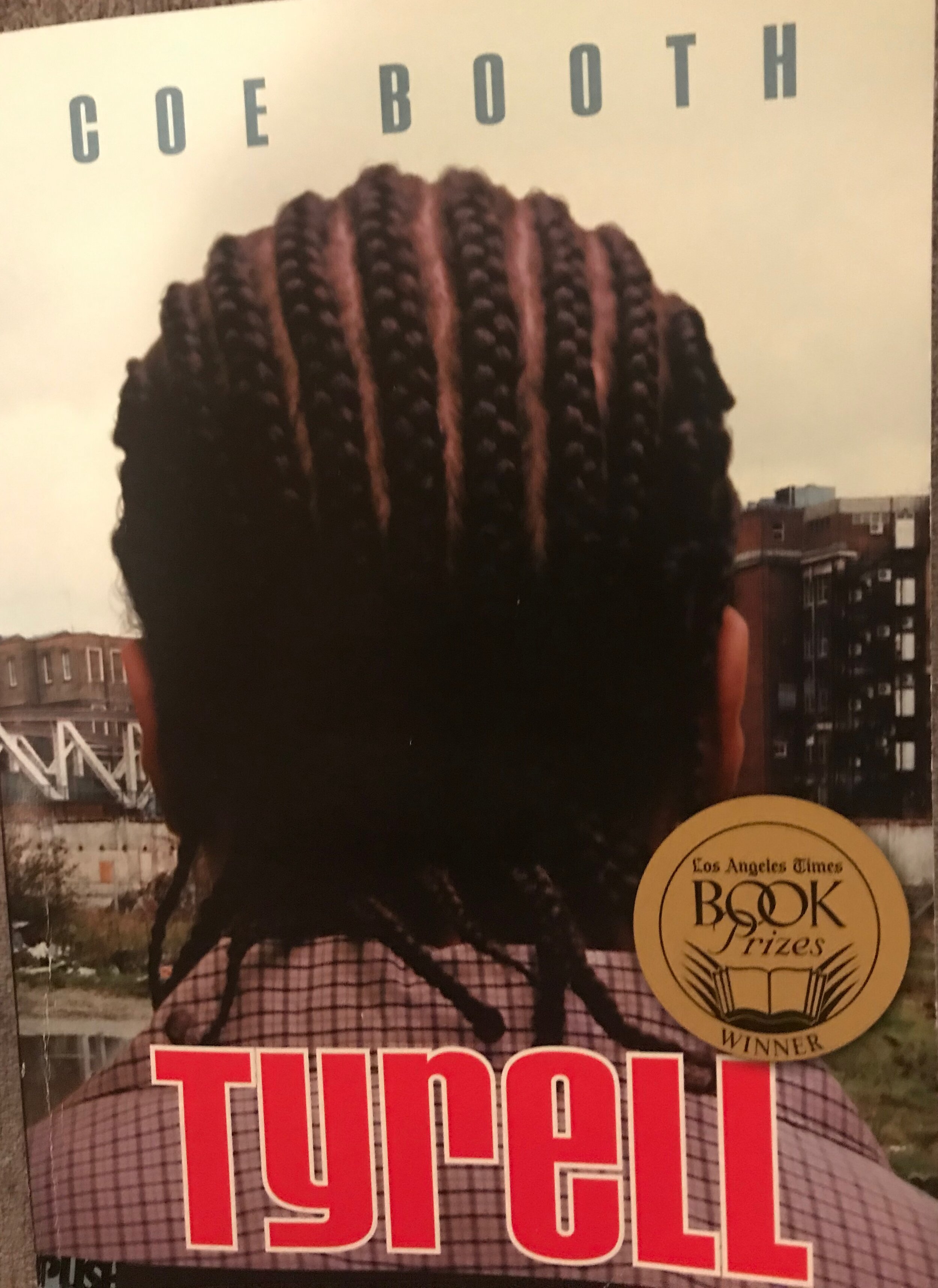

Tyrell

By Coe Booth

When I read Tyrell, I knew right away that I wanted to share my personal story and experiences with the child welfare system and social services. I started working for a child placement agency while I was getting my graduate degree in Literature. I was a single mom of a baby and I needed to supplement my student loans. I eventually became director and co-owner of Kids’ Resource Network, Inc., which afforded me the opportunity to work from home with my young daughter. I worked there for twelve years when, for a multitude of reasons, my co-owner and I both realized we were burnt out and decided to sell the business. As anyone working in social services can attest, it can be a really brutal job. Between the unending bureaucracy of the “system” and the horrific stories of child abuse and neglect, there are also sometimes extraordinary moments of watching love in action -- on the part of foster parents, social workers, and the biological parents, and primarily the children caught up in something many of them can’t even begin to fully comprehend.

One of the days that cemented my decision to do a different kind of work bore witness to the gamut of emotions at play for all the people involved in the child welfare system. Two of our foster parents – one a police officer, the other an employee of the sheriff’s department – got involved in a domestic violence altercation. They apparently forgot that because background checks were required as part of becoming a certified foster parent, we would immediately be alerted by the Bureau of Investigation if the police were ever called to the home. They had two foster children in their home, and we needed to remove them immediately. I drove down to Denver to meet the social worker at the house. As I neared their address, my partner called me and agitatedly told me that we had seemingly forgotten that we were removing kids from a home with parents who had firearms, and that we needed to insure that the police also meet us there. So we all converged on this house: social worker, cops, and me. Thankfully, there was no drama. The young kids exited the home, all their life belongings thrown in two black plastic garbage bags, and then shoved into the trunk of the social worker’s car. She took the kids off to their next temporary stay until we could come up with a more permanent situation. Returning to their biological parents was unfortunately not a viable option. The police dealt with the foster parents, whose certification was immediately revoked by our agency and the State. I drove home to my house in Boulder where I lived with my family that had grown to include a husband and another daughter. It was impossible then, and is impossible now, not to think of how differently the system had worked for me in a way that it had not for so many others.

At 27, I became pregnant with my oldest daughter, now 27 herself. I lived in San Francisco and worked very odd jobs. I barely got by and definitely could not afford health insurance. I applied for California Medicaid, and had phenomenally good healthcare throughout my pregnancy, delivering my daughter via C-section at the University of San Francisco under the care of an excellent obstetric practice. Because I had admitted to having smoking marijuana prior to my pregnancy, and because I was under the care of the State, the “system” immediately was involved, and tried to take urine samples from my baby daughter to confirm there were no other drugs in her system. I used my white privilege, threw a fit, and had my way. They had monitored me throughout my pregnancy and knew that I was clean, so there was absolutely no reason to disturb my baby other than that it was a bureaucratic measure. My then white boyfriend, an attorney, was also by my side. Had my daughter’s Black biological father been there, I wonder if they would have left us alone as they did. I went home four days later. Shortly after, I moved to Connecticut and once again applied for State healthcare. It was an experience that made me privy to how terrible the system can be. I did not want child support from my daughter’s biological father. I had left him because he had been abusive and did not want him involved in our lives. I learned quickly that if I wanted healthcare from the State, I would not be allowed to make that decision. At a meeting with a social worker, she told me I needed to tell them his name. I refused, and raised the hypothetical suggestion that I did not know who he was. They then quite snidely told me to give them a list of all the men I had slept with in that year, and they would test them for DNA. I was astounded by the way they spoke to me and found it deeply humiliating. But, unlike so many other women in my situation, I had other options. I was an Ivy league educated white woman. I had two employed parents who wanted to help me, even if it was embarrassing to have to go ask them for help. But ask I did, and I suddenly had private health insurance and the State out of my business.

The best part of being director of Kids’ Resource Network, Inc. were the monthly family meetings I had with the foster parents and the kids in their care. The majority of our foster kids were Black or Latinx. The parents were primarily white and Black, almost all of them religious Christians. As a private agency, we required substantially more training than the State, and we also provided significantly more supervision. They had visits from the State social worker once a month, and visits from our staff at least twice a month, in addition to therapeutic care. By the time we sold KRN, the differences between State and private child placement agencies had narrowed significantly. Private agencies had been required to become nonprofits, and were no longer given the huge subsidies that had allowed them to pay foster parents sometimes double what State parents had been paid, or to provide the kinds of services we had in the past. On top of that, the level of care had changed. In the Bush era, in an effort to save money, kids were released from expensive residential care facilities and placed in foster homes, many of whom simply did not have the training to take care of these kids with extremely high needs. Our foster parents were utterly overwhelmed. This was the case across the State. The luckiest kids had a good guardian ad litem advocating for them. A lot of the kids, unfortunately, fell through the cracks. (This 2002 article about Florida’s foster care system, tells of kids who actually got lost in the system. Thankfully, this was not something we experienced in the years I worked in Colorado).

Booth’s young adult novel speaks to the systemic racism plaguing the US. As this article on “Race and Class in the Child Welfare System” makes clear:

“a national study of child protective services by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported that ‘minority children, and in particular African American children, are more likely to be in foster care placement than receive in-home services, even when they have the same problems and characteristics as white children’ [emphasis added].”

A serious reading of Tyrell requires engagement with the criminal justice system as well, especially the school to prison pipeline, as described so vividly by Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow. The circumstances of fathers like those of Cal’s and Tyrell’s are hardly unique. While the rates of Blacks in prison is declining, this recent Pew Research Report includes these alarming statistics:

“Black men are especially likely to be imprisoned. There were 2,272 inmates per 100,000 black men in 2018, compared with 1,018 inmates per 100,000 Hispanic men and 392 inmates per 100,000 white men. The rate was even higher among black men in certain age groups: Among those ages 35 to 39, for example, about one-in-twenty black men were in state or federal prison in 2018 (5,008 inmates for every 100,000 black men in this age group). The racial and ethnic makeup of U.S. prisons continues to look substantially different from the demographics of the country as a whole. In 2018, black Americans represented 33% of the sentenced prison population, nearly triple their 12% share of the U.S. adult population.”

The statistics on homelessness for youth identifying as Black, indigenous, and people of color, are just as alarming. Although Blacks make up only 13% of the US population, another recent Pew report indicates that:

“Twenty-one percent of people living in poverty in the United States are black [and that] African-Americans account for 40 percent of people experiencing homelessness — and half of homeless families with children, according to the 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR), produced by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. American Indians also are overrepresented in the homeless population.”

The National Alliance to End Homelessness cites similar statistics. The National Network For Youth speaks specifically to the plight of homeless youth of color, and how they are affected by policies of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, including some of what Coe Booth depicts in this novel:

“The definition of homelessness for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Developments’ Homelessness Assistance Grant program definition of homelessness excludes most children and youth whose families pay for a motel room, or who must stay with other people temporarily, because there is nowhere else to go. These situations are unstable and often unsafe, putting children and youth at high risk of trafficking and violence. Under HUD’s definition, children and youth in such living situations are not even assessed for services. Other federal programs recognize that children and youth in such living situations are homeless. This definition disproportionately harms youth and families of color.”

Tyrell speaks to something else that I witnessed while working for Kids’ Resource Network, Inc., and that is that for all the horrors experienced by displaced children, there continue to be moments of love and joy that are all too often ignored. Sometimes these moments take place between a foster child and a caring social worker or a loving foster parent, but there is also the deep love that is evinced by a child with their parent during a supervised visit, or a visit to a parent in prison. Booth captures the complexity of these kids’ lives in Tyrell. The novel ends on this note: “It feel good coming back home to the projects. Where I belong.” Booth complicates the notion of home and the systems designed to protect children. In addition to highlighting the vast dangers confronting children in the system, Booth’s novel also refuses to downplay what the poet Nikki Giovanni recognized and evokes so exquisitely in her poem, “Nikki-Rosa.”

childhood remembrances are always a drag

if you’re Black

you always remember things like living in Woodlawn

with no inside toilet

and if you become famous or something

they never talk about how happy you were to have

your mother

all to yourself and

how good the water felt when you got your bath

from one of those

big tubs that folk in chicago barbecue in

and somehow when you talk about home

it never gets across how much you

understood their feelings

as the whole family attended meetings about Hollydale

and even though you remember

your biographers never understand

your father’s pain as he sells his stock

and another dream goes

And though you’re poor it isn’t poverty that

concerns you

and though they fought a lot

it isn’t your father’s drinking that makes any difference

but only that everybody is together and you

and your sister have happy birthdays and very good

Christmases

and I really hope no white person ever has cause

to write about me

because they never understand

Black love is Black wealth and they’ll

probably talk about my hard childhood

and never understand that

all the while I was quite happy