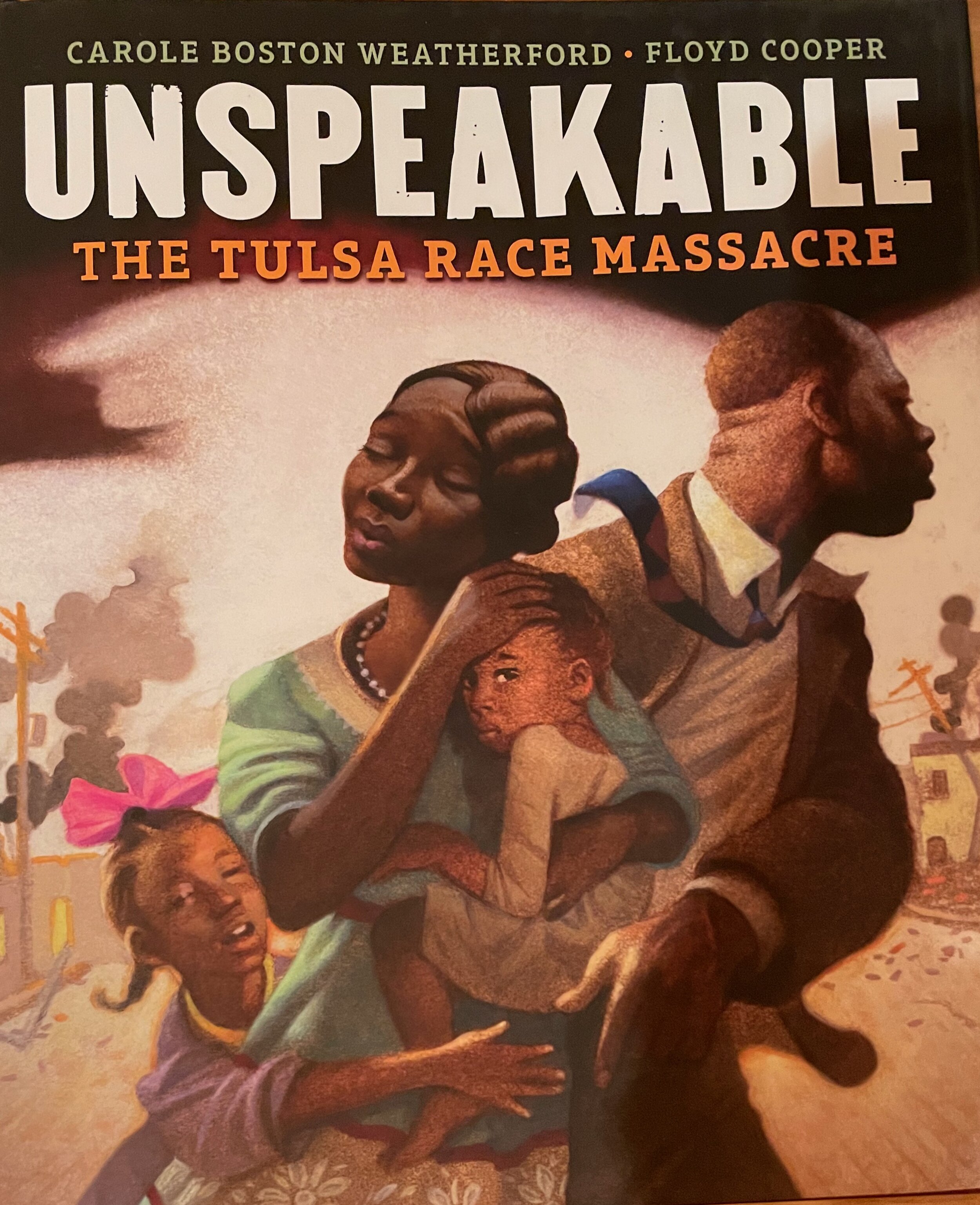

Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre

By Carole Boston Weatherford

Language is important. Carole Boston Weatherford recognizes this and appropriately calls what happened in Tulsa on May 31-June 1, 1921 a massacre and not a riot. (This specificity in language will also be discussed in the write-up on Traci Chee’s We Are Not Free when thinking about the words interment/ incarceration/ concentration camps with reference to the experience of Japanese Americans in World War II). As Woodward and the illustrator Floyd Cooper attest, the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre was not taught in schools until the 21st century. I most certainly did not learn of it growing up. (A documentary about it, produced by LeBron James and writer/director Salima Koroma, is currently in the works, and Victor Luckerson writes a newsletter on Substack called “Run It Back” about the research he has been doing for his upcoming book, Built From The Fire. You can read an interview with him here).

I initially read this book right around January 6, 2021, the date of the notorious attack on the Capital. Weatherford’s ability to conjure a mob mentality rang frighteningly true. She is direct, and yet the book is not intimidating for younger readers. She is gentle in describing the trigger of the massacre (an accusation of assault by a 17-year-old white girl). More mature readers will understand the deeper history of the visceral damage of such accusations (e.g., the lynching of Emmett Till and too many other Black men falsely accused due to white dread of miscegenation). Cooper’s art leaves space for Weatherford’s words to be elaborated on by parents and teachers. What I hope will be emphasized and discussed is the inarguable fact that “the police did nothing to protect the Black community.” It is an opening to a much longer discussion of police presence in Black communities, the systemic issues plaguing the criminal justice system, and the continued racism directed towards Blacks in America, no matter their level of success. Weatherford’s book also opens the door to discussing the complexity of race in America. As she writes, Greenwood “residents descended from Black Indians/ from formerly enslaved people, & from Exodusters.” Had you heard the word Exodusters before? I hadn’t! But I will not now forget it (please note that both sites above have educational resources and teaching plans).

I loved Weatherford’s use of a fairytale form with her repetition of “once upon a time…” It is an understandable literary structure: it contains the ability to present the magic of what was the Greenwood community, and the tragedy of what befell it. At its peak, it represented the heights of Black progress in America, albeit fully segregated. This “community called Greenwood” – 10,000 people -- with its one mile stretch of Greenwood Avenue – the “Negro Wall Street of America” as Booker T. Washington called it – was home to two Black-owned newspapers; the largest Black-owned hotel in the country; a Black-owned movie theatre; multiple other businesses, including the medical practice of Dr. A.C. Jackson; and successful schools (“some say Black children got a better education than whites” – certainly an unusual phenomenon in the US at the time, and a continuing problem now. See, for example, this New York Times article on segregation in NYC schools and listen to the podcast Nice White Parents). And, since fairytales inevitably contain terror as well as wonder, it all came tumbling down, destroyed at the whim of white people, and resulting in the deaths of over 300 Black citizens, with the burial sites of most of the victims never found. Weatherford tells this story with the utmost grace. Her author’s note and Cooper’s note personalize this history. Cooper actually spent his childhood in Tulsa and learned of it only through oral history – he never heard of what happened from his teachers. Weatherford writes about the painful history of lynchings in her own family; the Black Wall Street in Durham; and the Wilmington Massacre of 1898.

How do we share such history with children? How do we, as adults, help children make sense of words like “patriotism” and “safety” in the context of brutal aspects of American history that have long not been taught (and that perhaps many of us had not even heard of)? We start, I think, by refusing to cover it up any longer, by exposing it, by speaking the truth. Reconciliation cannot begin until that happens, and we need to invest in the hope that with these tellings, our children will be driven to insure that this history does not repeat itself. By telling the story, we make our children witnesses. I believe this is a hard but necessary burden, and it entails the belief that children can bear up under the weight of truth. Authors like Carole Boston Weatherford, dedicated to writing for children, understand the necessity of this. In book after book, Weatherford navigates truth-telling to children, the necessity of sharing history.

Weatherford’s catalog of books is pretty phenomenal, and Good Trouble For Kids is proud to be featuring some of them, including Gordon Parks: How the Photographer Captured Black and White America and Fannie Hamer: Voice of Freedom.

In Kwame Alexander’s phenomenal children’s book The Undefeated, (featured by Good Trouble For Kids in January 2021), two pages are devoted to art alongside the words “this is for the unspeakable.” Alexander’s end note indicates that the unspeakable includes the millions killed during the middle passage; the 16th Street Baptist church bombing; and the police murders of young Blacks, including Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Trayvon Martin. As I wrote in my write-up, the pages are a way of introducing the idea of memorialization and tribute to young readers, and the art and words are meant to evoke questions. The very same can be said of Weatherford’s book, with its addition of the Tulsa Massacre to what has been deemed “unspeakable.”

The poet Sharon Olds wrote her poem, “Race Riot, Tulsa, 1921” in response to a photograph from the Tulsa Massacre. You can see her poem and the photograph on the website 20th & 21st Century Protest Poetry: Poems That Make A Difference.

This poem below by Quaraysh Ali Lansana (link includes photo) draws a direct line between what happened in Tulsa to the hundreds-year history of racism in America, up to our own time. It is a powerful call to be an upstander and not a bystander; to be a witness and an activist; to use your voice. stir is the last word of this poem. I take that to mean make good trouble. Use your voice. Learn this history. Do not stand idly by.

“recipe for a massacre: tulsa 1921” by Quraysh Ali Lansana

I.

ingredients:

one economically and culturally thriving black community, the most vibrant of its

kind in the world. before harlem renaissanced. where at sunrise a dollar journeyed

from greenwood & archer to pine & back at sunset through thirty-six blocks of

black hands, black labor, black love on the black side of town.

one fourteen-year-old state that was point of origin & repository for the nation’s

earliest & largest ethnic cleansing actions that named jim crow attorney general (in

defiance of the president) & the ku klux klan its supreme court.

a racism that suspends all rational judgment.

a stumble in an elevator. a scream of rape from sarah page. a jail, dick rowland, for

your protection. a lynch mob. a defense mob. a gunshot. hate. a gunshot. hate. a

deputizing of hundreds. a machine gun on standpipe hill. a dropping of bombs

from chartered planes. a burning. little africa on fire. a marching at gunpoint. three

internment camps. three-hundred dead in the ruins of their own prosperity.

II.

and we can’t find the sun

six thousand limping from mcnulty

park, convention hall & fairgrounds

pray on just a little while longer

past our smoldering dreamland

past madame cj’s & tulsa star

past doctor jackson’s & vernon a.m.e.

toward the ghosts of our homes

front stairs to nowhere but tarred sky

III.

add a terrance crutcher. a trayvon martin. a philando castile. a bullet for your

protection. a columbine. a sandy hook. a stoneman-douglass. an ar-15 for your

protection. a dude in las vegas with an arsenal larger than the armory in enid. a nra

for your protection. a nobel prize winning scientist. a bell curve. an iowa senator’s

lips. a dodge challenger on fourth street in charlottesville. a unite the right rally for

your protection. a dylan storm roof at prayer service. a prayer. a prayer. a prayer.

he who passively accepts evil is as much involved in it as he who helps to perpetrate it. he

who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it, king said.

IV.

stir.